To honour the fact that Chelsea

It comes from a three-part

anthology entitled ‘Living London’

edited by George R Sims. If you’re unfamiliar with Sims, here is an article I wrote about him a couple of

Christmases ago, to celebrate his poem ‘In

the Workhouse, Christmas Day’

If you have an interest in London

The following article is

entitled ‘Football London’ and was written by Henry Leach:

|

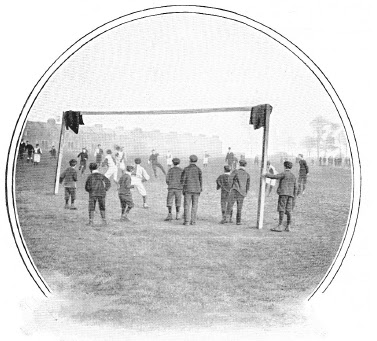

| In Battersea Park |

There is one section of London

There have been many eras of

London football, and of such stern stuff is the London London

Football in London rouses

itself from its summer's sleep less readily than it does in the provinces, where they keep a vigil on the

last night of August that they may the earlier kick the ball when September

dawns. In London

And so it happens that when Sandy

McTavish, the new forward, who has come all the way from Motherwell, Dumbarton,

or the Vale of Leven for four pounds a week, strips himself and bounds into the

ring for practice and for judgment, his feelings on analysis are found to be

much the same as those of the gladiator in the glorious days of Rome. Sandy Sandy Sandy Sandy Sandy London

And when the season opens,

away bound the professional teams like hounds unleashed, and every camp is

stirred with anxious thoughts. There is Tottenham Hotspur, who vindicated the

South after the period of darkness. Nowhere is there such enthusiasm as at Tottenham, where the bands

play and the spectators roar themselves hoarse when goals are scored, and

betake themselves in some numbers to the football hostelries when all is over

to fight the battle once again.

It is a football fever of

severe form which is abroad at Tottenham. Again, at Plumstead, where the Woolwich

Arsenal play – a club of many achievements and more disappointments. The

followers of the Reels, as they call them from their crimson shirts, are

amongst the most loyal in the land, and Woolwich led the way in the

resuscitation of the South. League clubs came to Plumstead when Tottenham was

little more than a name.

Over at Millwall is the club

of that name, which has likewise had its ups and downs, though they call it by

way of pseudonym the Millwall Lion. In the meantime, whilst these great teams,

and the others which are associated with them in London professionalism, play

the grand football, there are no lesser if younger enthusiasts by the thousand

in the streets and on the commons and in the parks, and their grade of show

ranges from the paper or the rag ball of first mention in this article to the full

paraphernalia of the Number Five leather case and the regulation goal posts and

net. And don't think this is not the most earnest football. If you do, stroll upon some Saturday in the

winter time into Battersea and Regent's Park, and there you will see the

youngsters striving for the honours of victory and for the points of their

minor Leagues. The London County Council makes provision for no fewer than

eight thousand of these football matches in its parks in a single season. And

at our London St. Paul 's Cathedral Choir School

|

And up at another great amateur headquarters, Tufnell Park, you should see a game between the renowned Casuals and the London Caledonians or "Caleys." That is the game to warm the blood of

a football follower. And at that historic spot which is known as the

"Spotted Dog," you will find the great Clapton team disport themselves.

These representatives of amateurism are

indeed great in their past, great in their traditions, even if they are not great

in the eyes of the Leagues.

The other notable and

enduring feature of London football is its Rugby section. It has a story all its own, and the Rugby enthusiast never could see anything in the “socker”

game. It is admitted that “rugger” is a cult, a superior cult, and though it

has its followers by thousands in London London has always held a glorious place in

the Rugby football world, and the public schools and the 'Varsities supply such

a constant infusion of good new blood, so that when the fame of Richmond and Blackheath fade away, we shall be

listening for the crack of Rugby doom.

And so the eight months'

season with its League games, its cup-ties, its 'Varsity matches, rolls along,

we round the Christmas corner with its football comicalities, and we come in

due course to the greatest day of all the football year, when the final tie

in the English Cup competition is fought

out at the Crystal Palace.

And so the eight months'

season with its League games, its cup-ties, its 'Varsity matches, rolls along,

we round the Christmas corner with its football comicalities, and we come in

due course to the greatest day of all the football year, when the final tie

in the English Cup competition is fought

out at the Crystal Palace.

It cannot be an exaggeration

to say that it is one of the sights of the London

At night, when the greatest

battle has been won and lost, he swarms over the

At night, when the greatest

battle has been won and lost, he swarms over the

I loved the experience and Sergio was an excellent instructor and a lovely guy to fly with.

ReplyDeletepleasure flight London