On 1st January 1900, Queen Victoria sat in her writing room at her desk in Osbourne House on the Isle of Wight. She was 80 years old and in her sixty-third year as Queen of the United Kingdom and Ireland and her twenty-fourth as Empress of India. She opened her journal knowing that she was in the final stages of life. She wrote:

“I begin today a new year and a new century, full of anxiety, and fear of what may be before us! May all near and dear ones be protected. I pray that God may spare me yet a short while to my children, friends and dear country…”

“A short while” she was indeed to be spared, and she saw in another new year twelve months later, but by then, all was not well with the ageing matriarch. The first entry in her journal for January 1901 was:

“Another year begun and I am feeling so weak and unwell that I enter upon it sadly.”

A few weeks later, on 14th January 1901, she was to receive a visit from Lord Roberts, field marshal of the British Army currently fighting an ugly and unimpressive campaign in South Africa against the Boers. He had returned to England to receive some of his many honours, leaving Kitchener in charge in South Africa.

After spending a little time with the Queen (whom he had also visited a fortnight prior to this meeting) 68 year old Roberts left, appearing shaken and emotional. He returned to the war office and cancelled all his arrangements and engagements for the foreseeable future. What had happened to upset this seasoned war campaigner? Roberts could not have known, of course, that he had just left what would be the last official engagement of Queen Victoria. Or did he sense that possibility?

People close to the Queen were puzzled by Roberts’ behaviour. She seemed to be her usual self to her family and staff; those she was closest to, but perhaps they were too close to her to notice the changes as she slowly deteriorated, and it took an occasional visitor to notice the differences that the Queen was going through between meetings.

Another visitor who noticed changes to the Queen was her German eye specialist; Dr Pagenstecher, who had served the Queen for a number of years – her eyesight being poor. He noted that since his last visit her eyesight had not got any worse, but her overall health had appeared to diminish considerably. He informed the Queen’s personal doctor; Sir James Reid.

|

| James Reid |

James Reid kept extensive and detailed notes and diaries of his contact with the Queen, and was in a position of trust with her, and a valued member of the Royal household. In his notes can be read his secret fears that the Queen’s mind was closing down; a process he called ‘cerebral degeneration’. He had noted that she found it difficult to concentrate and when she woke up in the mornings it took a few minutes for her to realise where she was and who the maids – her closest and most intimate servants – were.

For the first time in her service Reid saw and examined the Queen in her bed – his presence whilst she was in such an intimate state had previously been forbidden and against the etiquette regarding the Queen’s dignity. He had always examined her whilst she was upright, but on the morning of the 16th January, her maids became worried when she seemed unable to wake up properly. The breaking of the etiquette rule by Reid is something the Queen was likely to not have even noticed as she was incredibly drowsy. Reid noted that although she appeared unable to wake entirely from her dozing sleep, she appeared well enough on the whole.

Despite his generally positive diagnosis, Reid informed the Queen’s assistant private secretary; Fritz Ponsonby, that she was too ill to see anyone or receive telegrams or letters. Ponsonby – aware of the strict household rules – resisted the idea, but Reid eventually had the secretary begrudgingly agree to his wishes to withhold all meetings and correspondence with the Queen.

It was late in the evening before the Queen was awake enough to be moved from her bed and into her wheelchair, although she was still dazed and confused and her speech somewhat laboured and slurred. Reid brought in a second doctor, Sir Francis Laking – physician to the Prince of Wales, Edward Albert – to examine the Queen. After spending 45 minutes with her, Laking disagreed with the Royal Doctor’s diagnosis, and said to Reid that he believed the Queen was fine. He said she had talked to him with interest and vigour on a number of different topics and was ‘quite herself’.

The two doctors’ argued, with Reid suggesting that Laking tell the Prince of Wales that his mother was ill, but Laking refused and left. Reid feared that Laking had merely seen what he had wanted to see, or more accurately, what he wanted to tell the Prince of Wales.

|

| Fritz Ponsonby |

Within ten minutes of Laking leaving, Reid was called by the maids to see the Queen again. If Laking had stayed, Reid would have been able to question his diagnosis before him, as the elderly Queen was exhausted and confused. Reid grew angry and concerned that his efforts to inform the correct people of the seriousness of the Queen’s condition were being ignored. He took it upon himself to write to the Prince of Wales and tell him the truth.

Early morning on the 17th January Reid examined the Queen. His concern was growing; her face appeared flat down one side and she was even more drowsy and confused than the previous day; Indications that she had suffered a stroke. Reid recorded his fears in his diary;

‘I did not at all like her condition and thought she might die within a few days.’

He realised the enormity of the event that was about to occur and felt the responsibility of his role increase. Not only was Victoria his patient, but she was also the Queen and Empress. He had a duty to both care for her, and to let the public know what condition their monarch was in. After all, he knew that she may not be their monarch for much longer. He wrote:

‘being so anxious to prepare the public for what I feared was coming, and also thinking that her condition was too serious for it to be kept longer from the public, I thought a statement ought to be made in the Court Circular.’

The Court Circular was a list of announcements of events and news from the Royal Court given to the newspapers every day – the equivalent of what we today call a press release – and had been used for the whole of Victoria’s reign to keep the public informed on their Queen’s movements and activities such as honours she was bestowing and what esteemed visitors she was receiving. Ponsonby was tasked with ‘editing’ the circular so that the Queen herself could approve it before it was sent to Fleet Street in London to be placed in the papers. Despite the deteriorating health of the Queen, the circular never mentioned anything of the kind, and made it appear that everything was fine with the monarch, and even gave the impression that she was riding out in an open carriage down Newport high street in the unseasonably inclement January sunshine.

The circular was not complete fabrication – this carriage ride did happen, it just happened ten days earlier than reported. During it, the Queen had to be constantly awakened with coughs and tugs at her petticoats from her daughters. To avoid upsetting the public, the circular was merely “selectively edited”.

On 19th January (Incidentally, the day the Queen, aged 81 years and 240 days became Britain’s oldest ever monarch.) Reid’s concerns about her health were growing. Victoria had woken more confused than before, and as her breakfast was spooned into her mouth she appeared not to even realise that she was eating. She was growing weaker and her mind deteriorating before him with each day, yet her other aides, servants and even family appeared to be blind to the situation. Some even commented on how she appeared much brighter. Princess Helena; Victoria and Albert’s fifth child, wrote a telegram to her brother, the Prince of Wales, saying she was a lot happier about their mother’s condition.

Reid was appalled. He ordered that the Prince of Wales be telephoned at once and told that he should not go shooting in Sandringham as he planned, but stay in London, and be ready to get to the Isle of Wight. A train at Victoria station was readied for the Prince of Wales, and his sister, Princess Louise.

|

| Princess Helena |

Just over two hours later, The Royal Household at Osbourne was on tenterhooks. Amidst the distress over the fast approaching end of the Victorian era, there were many tasks to be carried out; the press had to be kept informed and arrangements made for the inevitable death. Ponsonby received message after message from concerned well-wishers; Lords and Ladies, Dukes and Duchesses and foreign dignitaries who were receiving the news. Members of the Royal family were arriving from all over the country and world in dribs and drabs, Osbourne was filling with people and food had to be arranged as well as sleeping arrangements. Carriages were on almost constant errands to meet visitors from ferries landing on the Isle. From Germany, the Kaiser, Victoria’s Grandson – son of Victoria and Albert’s eldest child Princess Victoria – was already on his way.

|

| Victoria's Grandson - The Kaiser |

By the 20th January the nation was aware of the news and the Empire fell into an expectant and fearful hush. On the tiny Isle of Wight, which had become the centre of that empire in the last few days, the Queen lay dying, surrounded by almost her whole family. In London, thousands of people turned up at St Paul’s Cathedral where prayers were held for ‘The Mother to Our Nation’. All around the country churches were filled with subjects thinking of the Queen. People congregated at Mansion House, Buckingham Palace and Marlborough House hoping for news and fearing the worst.

The Queen continued to decline and woke the following morning extremely confused and restless. Her breathing had become laboured and difficult and so was given an oxygen mask to help her. She could not move herself, and could not help those trying to move her in any way. Bulletins were issued regularly to the press outside Osbourne keeping them up to date with the Queen’s health. None of them contained good news. That evening, the Queen’s family surrounded her in her bed. She lay before them, hardly able to speak, breathing shallowly, struggling to swallow, barely conscious and barely recognising any of them.

At midnight, the Bishop of Winchester was woken by a loud knock at his door. When he went to see who it was he was met with a messenger from Ponsonby, who instructed him to come to Osbourne immediately. He was also told that he could expect to remain there. Reid knew the end was drawing near.

On Tuesday 22nd January Reid examined the Queen as her family stood anxiously about her bed. By now she could not swallow and her lungs were congested. Her cough was meek and as she breathed her windpipe rattled. Reid brought The Bishop of Winchester into the bedroom where he said prayers for Victoria with the family and Reid joining in. A bulletin was issued to the reporters outside at 4p.m which read:

‘The Queen is Slowly Sinking’

At 6p.m, with the Bishop dismissed, the Prince of Wales sat at his mother’s bedside in a chair as each member of the family took their turn to whisper their goodbyes’ in her ear.

At 6:25p.m the Bishop was called urgently back in, as he began to pray, Victoria looked up at Reid and the Prince of Wales, but the Bishop observed that she did not appear to look directly at the two men. An observation shared by Princess Helena:

‘Then came a great change of look and complete calmness. She opened her dear eyes quite wide, and one felt and knew she saw beyond the Border land and had seen and met all her loved ones.’

As Reid held the Queen’s wrist to feel for a pulse the Bishop finished administering the last rites. Victoria, Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Empress of India drew her last breath at exactly 6:30p.m on January 22nd 1901 as the bulletin presented to the press simply states. This example, from The London gazette:

The Queen’s death – due to the somewhat ‘rose tinted’ circulars issued to the press in the last few months of her life – came with seemingly little warning and caused huge shock to her subjects. The whole of the Empire was unsettled by the news. To us it may seem strange that her death had not been considered; she was a very old woman in an age where life expectancy in some cases was half of what we see today, and yet, despite her being that old, nobody appeared to have ever thought of, or even contemplated her not being there. She was a monarch that people had grown to depend upon; true as the sun will rise in the morning, the Queen will be on the throne.

For 64 years she had been Queen; most common Victorians could only dream of even living that long. In an ever changing world, the Queen was one constant.

All over the country, upon hearing the news of her death, people wept openly in the streets. The whole country was overcome with an immense sense of loss and fear for the future.

There was a mass outpouring of mourning. All adults dressed in black, banners of black and purple banners hung from shop windows and public areas where anything was painted black, such as iron railings were given fresh coats of black paint.

Eyes turned to the forthcoming funeral.

The Queen had often contemplated her death and thought of her funeral. Her wishes were for a Military style funeral as she was the head of the British Army.

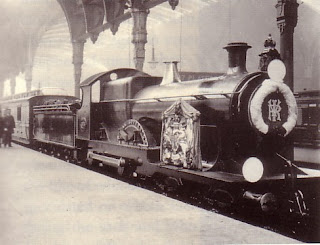

On the 1st February 1901, the coffin of Queen Victoria started its journey to her final resting place in Windsor, leaving Osbourne for the Royal yacht, Alberta, where it sailed to Portsmouth, accompanied by the sound of gunfire from the warships in the Solent. The Prince of Wales, Albert Edward – now King Edward VII at the age of 61 – followed behind. From there, the coffin was to make its way by train to London – appropriately arriving at Victoria station on 2nd February.

In London, immense crowds gathered about the station as the coffin – carried by gun carriage and decorated with the Imperial Crown, orb, sceptre and the collar of the Order of the Garter – made its procession through the soldier-lined streets. Behind the coffin followed the New King; Edward VII, along with a huge list of dignitaries from all over the world including the Queen’s Grandson, Kaiser Wilhelm II, King George I of the Hellenes, King Carlos of Portugal, King Leopold II of the Belgians and Archduke Franz Ferdinand to name a few. It was estimated that well over a million people from all classes and backgrounds had descended to London to bid farewell to the Queen.

Princess Maud noted that despite the vast number of mourning subjects in London, not a sound emanated from the crowds as the coffin passed them. From London, the coffin would travel to Winsdor on the Royal train from Paddington station

On 4th February crowds gathered in Windsor and wept as they watched the gun carriage carry the Queen's coffin from the train station to Windsor Castle, where it was to lay in state in the Albert Memorial Chapel. From there, the Queen was accompanied by her family to the mausoleum where she was to be laid to rest next to her husband, Albert, who had died 40 years earlier - an event the Queen had mourned for the rest of her long life. After a moving service and the Blessing in the Mausoleum, the Royal family passed in single file over the platform overlooking the grave containing the two coffins of Victoria and Albert side by side. The new King knelt by the grave with his wife and young son, in silence for a few minutes, before walking on.

A white stone figure of the Queen had been sculpted by Baron Marochetti at the same time as he had sculpted the figure of Prince Albert which had lay upon his grave since his death in 1861. The figure of the Queen had been stored, laying in wait for her death for forty years, until now. The figure of the Queen was placed on the tomb so that Queen Victoria’s face was inclined to Prince Albert, the love of her life, with whom she was, at last after forty long years, reunited.

The subjects of the old Queen had followed many of her fashions, one of which being extensive mourning. As the public geared up for a long period of wearing black in honour of Victoria, her son King Edward VII limited the period of mourning for his mother to three months.

When mourning finished, the empire the old Queen had presided over reflected on its past and contemplated its future. The Boer War, which had not been going particularly well for the British, appeared as a metaphor for the state of the Empire in general. The military, which had conquered vast swathes of the world over the last century, now appeared incompetent, along with the politicians in government. The Queen’s death appeared to signal the end of the all-conquering British mentality, particularly in government, where things were not going completely according to plan in India or Ireland, which would soon lead to huge reforms in the former, and the Empire losing the latter. Even further down the line, the First World War would rock the vulnerable Empire even further, and lead to future events that would eventually see the British Empire diminish and crumble. Victoria’s reign was a reign of no compromise in any quarter – military, political, scientific and social, and an age of so many advances that we are certain to never see its like again. The reign of Edward VII, from 1901 (official coronation in August 1902) until his death in 1910 meant a new era, and one which would be completely different to all that had gone before.

It’s interesting to read what the newspapers said the day after Queen Victoria died. Not only did they love the Queen, but there was a huge sense of pride and patriotic feeling for her era. The Times, in particular did this well, with an article I have posted below this one as a separate blog post; I didn’t want this one to be over long…

Today, 110 years after Victoria’s death the Empire is no more, and depending on which commentators or papers you read, Britain is, and has been for a long while, the desperate little sibling of all powerful America. It seems that with the death of the empire, the patriotic nature of the country suffered a fatal blow, and suffered until it eventually died out some time between the 1960’s and 70’s.

|

| Edward VII Coronation Portrait |

Of course, we are currently subjects of a long-reigning and elderly Queen, but the monarchy certainly doesn’t seem to be held in the high regard it was during Victoria’s reign, and quite possibly never will again. It seems to me a sad fact that once Queen Elizabeth passes, the Royal family ties that connect her to Victoria will be so diluted, antiquated and distant that the dissolution of the monarchy may be a step closer.

The kind of grief we saw when Princess Diana died is probably the only thing I can think of in my lifetime that may have come close to replicating the scenes in London in February 1901 as Queen Victoria made her last journey, and from exploring history, the death of Churchill in 1965 may be ‘in third place’ to put it crassly, but It will be interesting to see the scenes that take place when Queen Elizabeth passes on – a Queen who, in many ways is very similar to Victoria in terms of age and length of rein. Having said that, I must also add that I hope her reign lasts many a year from now.

Who knows what the country will be like when the Prince of Wales succeeds his mother to the throne (if he does) and mirrors the ascension of Edward VII – both men having waited a terrifically long time to become monarch. The country is certainly in a period of uncertainty and vulnerability – just as it was in 1901.

The ‘Hero’ of the story, Sir James Reid would, just over nine years later, be present at the death of the man by whom he stood as his mother passed away – King Edward. Just as with the death of Queen Victoria, Reid kept detailed and extensive notes over the course of the King’s four-day illness until his death after four days on 2nd May 1910.

Although he would remain with the Royal Family after Edward’s death as Physician-in-Ordinary to George V, his role as medical advisor to the Royal Family gradually ceased, although he remained a close friend to the Royal family, most notably to Queen Mary whom he attended in Scotland at Balmoral, the two becoming good friends who would ride out in carriages together and visit the tenants and cottagers, often taking tea. Sir Bertrand Dawson, a younger man, was Reid’s replacement as doctor to the monarch, and was the physician used most by George V.

In June 1923, James Reid suffered an attack of phlebitis – inflammation of a vein – and died five weeks later on 29th June at the age of 73. Lord Stamfordham wrote in The Times:

“Among the remarkable men of the later Victorian group, Sir James Reid stood somehow or other by himself. The niche which he created and filled remains in the truest sense inimitable”.